Printable PDF of LaPorta_72_93

I. Introduction: The Political Stakes of Eustache Le Noble’s Pasquinades

In a letter dated August 5, 1694, French chief of police Gabriel Nicolas de la Reynie confesses his incapacity to prevent the publication of satirical pamphlets penned by then-imprisoned aristocrat Eustache Le Noble:

Ce n’est pas la première fois qu’il a été défendu à cet auteur de mettre au jour des écrits de sa composition, ni la première fois qu’on a enlevé d’entre ses mains, pendant sa prison, les ouvrages de sa façon qu’il y vendait avec beaucoup de scandale. Il a toujours trouvé des protecteurs et des partisans qui ont cru qu’il était utile de laisser à cet homme la liberté d’écrire sur toutes sortes de matières. On ne saurait dire combien de manières il en a abusé, et à quel excès il ne s’est porté, ni répondre non plus qu’il se contienne à l’avenir. (Reynie)

This is not the first time that this author was forbidden from bringing to light his writings, nor the first time that someone removed from his hands, during his imprisonment, his works that he was scandalously selling there. He has always found protectors and supporters who found it useful to grant this man the freedom to write on all sorts of subject matters. One cannot say how many ways he has abused this freedom, and to what excess he has taken it, nor whether he will control himself in the future. (Reynie)

Even from the confines of his jail cell in the Conciergerie, Le Noble remained as elusive and subversive as his texts—an author whose “abuse of freedom” and penchant for “excess” paradoxically earned him both the contempt of royal authorities as well as the respect of high-powered protectors such as the Marquise de Maintenon (Godenne XII; Mangeot 73).[1]In this regard, it would seem that he upheld a family tradition initiated by his great-great-grandfather, Pierre I, who had also found ingenious ways to use the French throne to his own advantage (Hourcade 79). Beginning with his short career as procureur général in the Parliament of Metz in the 1670s, where he acquired a reputation as a reckless spender and a “dishonest adventurer,” Le Noble quickly became a politically rebellious figure, penning subversive poetry and serving several prison sentences before being banished in 1693 (24, 55).[2]Despite his notoriety and complicated relationship with the monarchy, Le Noble managed to earn a living from his pen during a period in which he was not only imprisoned, but also one in which authorship was only beginning to become a financially viable career (Cherbuliez 476; Mangeot 76). Le Noble was an extremely prolific, well-known author in his time, who published works in a wide variety of literary genres until his death in 1711.[3]

Although Nicolas de la Reynie remarks Le Noble’s extraordinary capacity to “bring to light” subversive publications from the placeof marginality par excellence, few literary scholars have attempted toelucidatethe political and ideological stakes of Le Noble’s pasquinades.[4] A collection of 142 satirical dialogues published anonymously between 1688 and 1694 and 1702 and 1709, these polemical texts achieved then-enormous press runs of up to six thousand (Klaits 146) and analyzed the affaires du temps with a combination of wit and historical accuracy.[5] If satire is a “perennially elusive, often paradoxical and contradictory, literary phenomenon” (Rosen 4), the pasquinade, by definition an anonymous lampoon, permits a more transgressive form of ridicule precisely because of the author’s capacity to figuratively hide behind his words. Named after Pasquino, a witty and sarcastic tailor who lived in Rome during the fifteenth century, the pasquinade tradition developed after Italians began to affix satirical placards onto a statue later discovered under the defunct tailor’s shop. The term pasquinade would later come to signify any kind of satirical attack, especially those against political authorities, whether posted to the statue of Pasquino or circulated as a manuscript (“Pasquinade”). It is the pasquinade’s particularly scathing nature that distinguishes it as a form of satire. Though written more than half a century after the texts in question, Diderot’s entry on “Pasquin” in the Encylopédie encapsulates the complicated status of the pasquinade during the ancien régime: “Cette licence qui dégénere quelquefois en libelles diffamatoires, n’épargne personne pas même les papes, & cependant elle est tolérée” (This license that sometimes degenerates into defamatory libels does not spare anyone, not even the popes, and yet it is tolerated) (“Pasquin”).

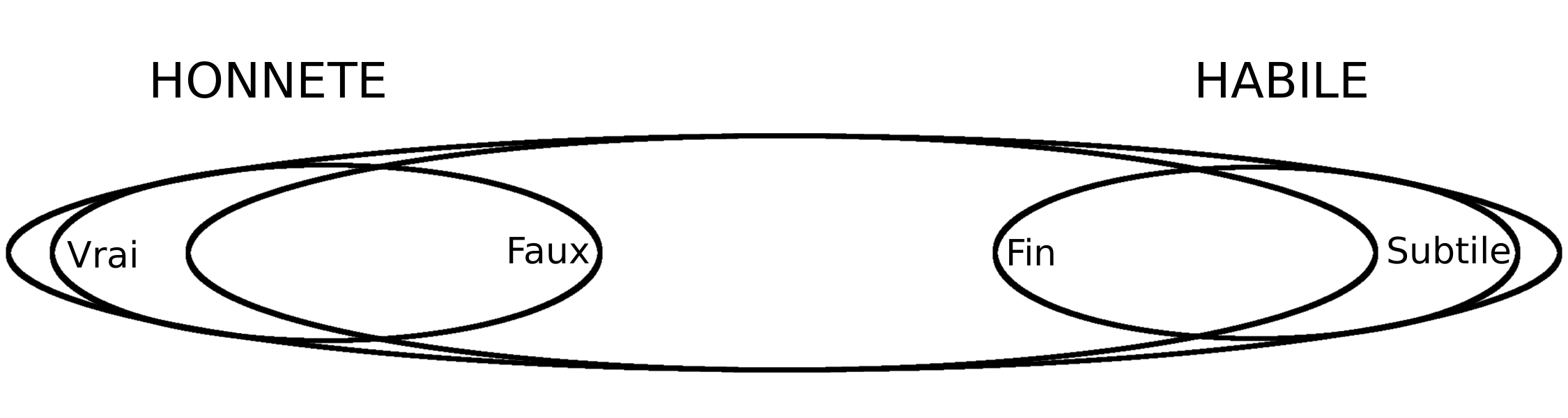

How are we to understand the “toleration” of Le Noble’s pasquinades within an increasingly centralized absolutist state that censored publications? True to the inherent license afforded by the pasquinade genre, Le Noble’s political dialogues derisively mock the enemies of French monarch Louis XIV, but they do so in a fundamentally dissimulative manner. Although La Pierre de touche politique dialogues deride the king’s rivals, the character traits for which these enemies are lambasted echo criticisms of Louis XIV advanced by the late seventeenth-century worldly intelligentsia. As we shall see, these pamphlets are readable as supporting and subverting the French crown, operating as propaganda on two levels: on the first level, they promote Louis XIV’s interests against England, the House of Austria, and the papacy. However, on a second level, the pasquinades question absolutism and examine the viability of other political organizations. The Pierre de touche politique pamphlets necessitate a careful analysis precisely because they operate on two levels of meaning, as we are reminded in a passage from one pamphlet that metonymically functions as a mise en garde for Le Noble’s dissimulative practices:“Conçois bien ce que je vais te dire, & tu verras que tu n’entres point dans le fond essentiel, mais que tu prends seulement la superficie des choses” (Hearwhat I’m telling you, & you will see that you do understand the heart of the matter,but that you are only grasping the superficial level of things) (La Fable 33). It is through this constant interplay between “le fond essentiel” and “la superficie des choses” that the pasquinades demonstrate satire’s particular effectiveness as a mode of critique in a politically repressive regime, as well as the specificity of Le Noble’s satirical techniques within the body of late seventeenth-century pamphlet literature. As we shall see, these works exploit dialogism both as a form and as a function, putting into place an interpretive structure whichmodels the type of active reading practice required to ascertain their meaning and ultimately demonstrating pamphlet literature’s importance as a space for critical reflection in fin-de-siècle France.

II. La Pierre de touche politique (1688–1691): Propaganda as a Double-edged Sword

Written during the early years of the controversial War of the Grand Alliance (1688–1697), the 29 pamphlets that compose La Pierre de touche politique shed light on the complexity of the publicity wars between Louis XIV and his foreign enemies. After evoking Lucian’s “prose satirique” as a model (La Bibliothèque 4), Le Noble explains the collection’s name through a simile claiming that his texts function like a “touchstone” that exposes the “truth” about European affairs:

[L]’on a jugé à propos de donner au corps entier de l’Ouvrage le titre général Pierre de Touche Politique, parce que comme cette Pierre par son attouchement découvre la pureté ou la fausseté de l’Or, aussi ces petits Dialogues tout en badinant découvrent toute la Politique sur laquelle roulent les affaires de l’Europe, & en démêlent le faible & le solide. (4)

One judged in this regard to give to the entire corpus the general title Political Touchstone, because like this Stone that through its touch reveals the purity or falseness of Gold, so also these little Dialogues, while bantering, reveal the Politics driving the affairs of Europe and separate the weak and the solid therein. (4)

Even as he invokes tradition and his imitation of Lucianic “satirical prose,” however, Le Noble also aligns with the modern values of innovation and emulation, immediately distinguishing his project from that of the Greek satirist by insisting on the political and historical importanceof the “vérités secrètes” revealed in his dialogues (3). Just as early authors of the nouvelle historique claim to reveal “a secret history” of political events as a pretext to rewrite and undermine the royal historiographers whose works they supposedly imitate, Le Noble likewise insists upon the veracity of his textsand exalts his dialogues as “une Boussole pour les Historiens futurs” (a Compass for future Historians) (Le Cibisme 4–5).[6]Furthermore, as if to signal the imperative to question authority within his satirical enterprise, the epigraph preceding each pamphlet reformulates an element of the Horatian utile dulci principle. Whereas Horace famously defends his own literary practices through the expression “Ridendo dicere verum quid vetat” (What forbids telling the truth with a smile) (Satires 1.1.24–25), Le Noble’s epigraph replaces the word “quid” with “nil”: “Ridendo dicere verum/Nil vetat?” (Does nothing forbid telling the truth with a smile?). By transforming Horace’s assertion into a more audacious interrogative, Le Noble emphasizes the fact that one can tell the truth with a smile in any circumstance—that is, even when it is told only inadvertently. As Helen Harrison has argued, Le Noble’s reformulation likewise seems “to point to the lack of control over unauthorized texts [in circulation] or to ask what limits, if any, will be placed on his mockery” (np). In these ways, the paratext to the Pierre de touche politique dialogues not only emphasizes the relative truth-value of historiography, but also underscores the “slippery” nature of satire and the dissemination of such works in late seventeenth-century France and Europe.

Each dialogue in La Pierre de touche politique adopts a particular polemical tone,which, on a first level, attempts to influence public opinion in Europe and France by promoting the French crown’s interests against England, the House of Austria, the papacy, and other members of the Grand Alliance. Indeed, the majority of the Pierre de touche politique dialogues ridicule Louis XIV’s two most significant religious and political rivals: Pope Innocent XI, against whom the French monarch struggled for spiritual authority within his borders (Ott 21), and William of Orange, who ruled as both Stadtholder of the Dutch Republic and King William III of England after the Glorious Revolution of 1688–1689 (Israel 646, 849–852).[7] Throughout the collection, Louis XIV is universally depicted as the victim of Pope Innocent XI’s “pernicious hatred” (Le Cibisme 23) and William III of England’s “consuming ambition” (La Fable 26), a pawn in a “universal political conspiracy” orchestrated by his enemies against him (Le Cibisme3).[8] The pope is treated as a heretic and a false Christian (16) who does not have “un grain de Catholicon dans le cœur” (an ounce of Catholicon in his heart) (26), whereas William of Orange, alternately dubbed “Guillemot” and “Jus d’Orange,” is repeatedly criticized for having usurped the British crown (Le Festin 12) and for the “absolute authority” with which he governs (La Fable 23). Whether or not the French crown financially endorsed Le Noble’s pasquinades, as some have speculated, it is clear that Louis XIV would have benefited from Le Noble’s humorous and scathing depictions of his political rivals.[9]

At moments, however, the lampoons against Innocent XI converge with criticism of Louis XIV’s own abuses of authority, and the figure of the pope is deployed to criticize forms of absolutism in general. In Le Cibisme (1689), for example,two fictional interlocutors, Pasquin and Marforio, analyze conciliarism—a doctrine that upholds the supremacy of an ecclesiastical council over the pope’s authority in spiritual matters (Örsy 56)—completely rewriting Catholic dogma and critiquing the papacy at its foundations. After arguing that papal infallibility is a falsehood (Le Cibisme 16), Pasquin questions the divine source of pontifical authority in terms that resonate with the universality of a maxim: “il n’est pas croyable que Dieu donne à un seul homme la droiture des décisions, & qu’il la refuse à un nombre innombrable de Pères assemblés en un Concile” (It is not plausible that God gives to only one man fairness in decision-making, & and that he refuses it to an innumerable number of Fathers assembled in a Council) (32). While the praise of conciliarism throughout Le Cibisme would have supported Louis XIV’s struggle with the Holy See, this in fact veils the underlying critique of all forms of government that rely on the supremacy of a divinely-appointed leader. By blurring the line the between papal and monarchical authority through the derision of “infallible” rulers who reign “alone,” Le Noble’s pamphletreads as an accusation against all leaders invoking the sacred origin of their power to command the absolute obedience of their subjects. In these respects, the mockery of papal authority undermines the French king’s own claim to “divine right to rule,” with the universality of the anti-absolutist criticism overshadowing the anti-papal content.

A later passage more closely evokes absolutist theory by ridiculing political structures based upon the primacy of the head of state over the body politic. Perhaps more significantly, this critique of the absolutist model redeploys the very terminology used to denounce Louis XIV in anti-monarchical pamphlets from the same period. In Les Soupirs de la France Esclave (1689), for instance, the anonymous author defends the original “Aristocratic” form of the French government in which the monarch would consult his Estates General before all important decisions (95–96),[10] arguing that the king’s sovereignty is lesser thanthat of the assembled États: “les Rois ne pouvaient rien sans [les États]; & au contraire...[les États] pouvaient tout sans les Rois” (Kings cannot do anything without the Estates; & on the contrary... the Estates can do everything without Kings) (96). In strikingly similar language, Le Noble’s characters uphold the supremacy of an assembled councilin religious matters:

Le Concile assemblé est le véritable Corps entier de l’Église, l’Évêque de Rome n’en est que le Chef, & il est ridicule de prétendre que le Chef, soit lui seul plus que le Corps entier qui comprend tout ensemble & le Chef & les membres: le Pape ne peut être sans l’Église ni hors l’Église, mais l’Église à chaque mutation de Pontificat subsiste sans Pape. (Le Cibisme 33, emphasis added)

The assembled Council is the true Body of the Church, the Bishop of Rome is only its Leader, & it is ridiculous to contend that the Leader, should be himself more than the entire Body which includes both the Leader and the members: the Pope cannot exist without the Church nor outside of the Church, but the Church subsists without the Pope in every variation of the Pontificate.(Le Cibisme 33, emphasis added)

Here, the denunciation of papal authority masks the implicit criticism of all forms of absolute power, with the satirized object vacillating between the particular (the organization of the Catholic church) and the universal (all absolutist political structures). Far from operating in a unidirectional manner, the propaganda in La Pierre de touche politique is a double-edged sword, lambasting the absolutist tendencies of a specific sovereign while also echoing the condemnation of Louis XIV’s own abuses of power.

Just as the Church and the State formed a two-sided edifice of power in the ancien régime, Le Noble’s pasquinades take aim at the spiritual domain of the papacy and the temporal realm of monarchy, using satire as a vehicle for political theorization. Even if the dialogical form and satirical nature of the pasquinades resist a straightforward interpretation of the author’s political beliefs, the discussion of socio-political regimes within Le Noble’s texts nevertheless resembles the typological analyses found in early modern political philosophy. In La Fable du Renard (1690), for example, the allegorical dialogue between the two “puissantes Républiques” of Switzerland and Holland assails William of Orange’s “usurpation” of the British crown and the enslavement of his subjects (8). Indeed,the “fortunes” of the populace may be inherently more unstable in a monarchy because they are vested in and literally subjected to the ever-changing personal inclinations of the king (32–33), but the interlocutors draw a distinction between standard monarchical governments and tyrannical states ruled by a “usurper” who has “no right” to the throne. From the outset of the pamphlet, Switzerland warns Holland of the dangers of William III’s tyrannical impulses, insisting that the Stadtholder would like to reign as king within Dutch borders as well:

Tu ne dois pas douter qu’il ne soit ennemi né de ta liberté; il ne fait en cela que marcher sur les traces de ses Pères, & comme eux dévoré d’ambition, il n’a d’autres soins n’y d’autre but que d’abolir ton Gouvernement, pour arriver à la Souveraineté absolue de tes Provinces. (26)

You should not doubt that he isthe born enemy of your liberty; in this respect he merely follows in the footsteps of his Forefathers, & like them devoured by ambition, he has neither other cares nor other goal but to abolish your Government, in order to arrive at the absolute Sovereignty of your Provinces. (26)

Later, Switzerland’s words pronounce the enslavement of the Dutch to “Tiny Will” as a rhetorical strategy to render its advice more compelling, even as they (incorrectly) predict William III’sultimate fall in England by deploying maxim-like phrases regarding the abuse of authority:

Toute l’Europe ne te regarde plus que comme l’esclave d’un Tyran qui t’a mise aux fers... mais je suis bien trompée si dans peu tu ne vois tomber ce Pygmée qui a marché à pas de Géant à l’Usurpation d’un Trône sur lequel il n’a aucun droit. Plus un homme acquiert d’autorité plus il en abuse, & l’abus que cet Usurpateur fait déjà de celle qu’il s’est donnée sur un peuple fier, volage & impatient, ne peut manquer de le renverser bien tôt de la place qu’il a perfidement envahi: Qui habitat in caelis irvadebit & subsannabit, & adhut pussillum, non erit. (44, emphasis in original).[11]

All of Europe now considers you the slave to a Tyrant who has put you in chains… but I am indeed mistaken if in a short time you do not see the fall of this Pygmy who has walked in Giant steps to the Usurpation of a Throne to which he has no right. The more a man acquires authority, the more he abuses it, & the abuse that this Usurper has already committed of the authority that he has taken over aproud,fickle, & impatient people cannot fail to reverse him soon from the place that he perfidiously invaded: He that sitteth in the heavens shall laugh & shall have them in derision, & in just a little while, will be no more. (44, emphasis in original)

This humorous critique of “William the Pygmy” functions as a general warning to monarchs who have misused their political clout, thereby playing on the thresholdbetween satire and political theory. Switzerland’s insistence that the Dutch have been “enslaved” by Tiny Will functions as a general warning against kings who have misused their political clout, who have crossed the line from monarchy into tyranny, or worse, into the realm of the despotic.[12]

This ambiguity between monarch, tyrant, and despot occurs elsewhere in the Pierre de touche politique collection, although the distance between William III and Louis XIV is here blurred even further. Throughout Le Festin de Guillemot (1689) and Le Couronnement de Guillemot et de Guillemette (1689), Pasquin and Marforio mock the extravagant baroque coronation ceremony organized by the “tyrant” William of Orange, as well as the paintings he commissioned to commemorate his so-called heroism (Le Couronnement 14) in terms that recallLouis XIV’s own self-aggrandizing propaganda.[13] In claiming that the English have fallen victim to a monarch who has “bankrupted” his nation’s treasury and infringed upon his subjects’ religious beliefs (34–35), the interlocutors warn against the concentration of power in the hand of the monarch and the corresponding weakening of parliamentary structures. As Pasquin and Marforio argue, the English—particularly the aristocrats—have been “put to sleep” by the usurper “Tiny Will”:

Pasquin: Toutes les Soupes dont [la Table] était couverte, ne consistaient qu’en une infinité de différents déguisements d’un fin Jus de Pavot artificieusement médicamenté, & très propre pour endormir les Mulots.

Marforio: Dis-les Mylords: car le proverbe est à présent changé, & au lieu de dire Endormir le Mulot, on dit Endormir le Mylord, pour exprimer qu’on fait ses affaires aux dépens du sot qui se laisse amuser. (Le Festin 26, emphasis in original)

Pasquin: All the Soups covering [the Table], consisted only of an infinity of different disguises of a fine, artificially medicated Poppy Juice, very appropriate to put the Fieldmice to sleep.

Marforio: Call them Mylords: because the proverb is presently changed, & instead of saying To put the Fieldmice to sleep, one says To put the Mylord to sleep, to express that one does his business at the expense of the fool who lets himself be amused. (Le Festin 26, emphasis in original)

In these respects, the dialogues within La Pierre de touche politique warn against the total erosion of liberty within states governed by “arbitrary and supertyrannical” rulers in which “duped” subjects are “enslaved” to their tyrannical leaders (Le Couronnement 45).[14]

In the same way that the denunciation of Pope Innocent XI’s unilateral authority recalls similar critiques of Louis XIV’s brand of absolutism in other pamphlets from the period, the mockery of William of Orange’s despotic tendencies is particularly subversive in light of the intellectualclimate of the pasquinades. As Melvin Richter has argued, the term “despotic monarchy” was coined to condemn Louis XIV’s arbitrary political policies and interference in the religious realm: “After the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, French Huguenots in Holland and England began to use the term despotique for the polemical purposes of comparing the absolutism of Louis XIV to that of the Turkish Grand Seigneur” (18).[15]Les Soupirs de la France Esclave, for one,is unequivocal in its condemnation of the state’s undue meddling in religious affairs. After lamenting the bellicose French monarch’s capacity to send his subjects to death on a battlefield, the author summarizes the nefarious effects of the “monster” of “Absolute Power” (10) in the following manner:

Toutes ces preuves font voir que la Puissance Despotique & Arbitraire du Gouvernement de France s’étend sans réserve & sur nos biens & sur nos vies. Je ne vois donc plus rien qui soit à couvert. Dirons-nous qu’au moins la conscience & la Religion sont à Dieu & à nous? Point du tout... Le Roi est maître non seulement de la vie & des biens, mais aussi de l’extérieur de la Religion: tellement qu’il n’est permis à personne de faire profession d’aucune Religion que de celle qu’il plaît au Roi. (43–44, emphasis in original)

All of these proofs make it clear that the Despotic & Arbitrary Power of the French Government sprawls without reserve over our goods and our lives. I do not therefore see anything that is safe. Will we say that freedom of conscience and Religion existsbetween ourselves and God? Not at all... The King is master over not only our life and goods, but also over the exterior manifestations of Religion: such that it is not permitted to anyone to profess any Religion other than the one that pleases the King. (43–44, emphasis in original)

Unlike Les Soupirs and other political pamphlets circulating at the same historical moment in which Louis XIV’s reckless ambition is unequivocally denounced,[16]however, Eustache Le Noble’s pasquinades once again straddle the line between support and criticism of the French absolute monarchy. In this respect, if one can argue that the critique of William III simply mobilizes a late seventeenth-century rhetorical trope to denounce the abuses of monarchical authority, the interest of Le Noble’s particular brand of subversion stems from the double readability of his texts. By evoking the figure of a sovereign who considers the property of his subjects “[ses] Biens...propres” (Le Couronnement 41), who “bankrupts” his nation’s “Religion” and “Riches” (34–35), and whose extravagant divertissements aim to “put to sleep” the aristocracy, the Pierre de touche politique pamphlets recall criticisms of Louis XIV’s own arbitrary policies, from his mismanagement of the State’s finances, to the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, to his excessive fêtes at Versailles. While the rhetorical force of Pasquin and Marforio’s mockery of the English king’s despotic qualities results from the paronymic relationship between William and his alleged political mantra (“Iwil”) (33), the literary and political significance of the pasquinades as a whole derives from the complexity of their satirical system. Even as they denounce the French monarch’s rivals, Le Noble’s dialogues exploit the instability between the particular satirized object and the general satirical content, vacillating between surface-level ridicule and the deeper anti-monarchical undertones. Profiting from the fact that the king’s immediate frame of reference were his own political vendettas, Le Noble was able to draw the royal censors’ attention away from the salient denunciation of French absolutism implied in his critique of various late seventeenth-century political figures.

III. Prescriptive Politics: From the Denunciation of Absolutism to the Theorization of Republicanism:

In addition to condemning the abuses of absolutism, the Pierre de touche politique pamphletsalso examine the viability of non-monarchical forms of political organizations in a subversive manner. Whereas the former type of critique manipulates the boundaries between satirized object and satirical content, the same mechanism is elsewhere applied to slightly different ends. Throughout La Fable du Renard, for instance, Louis XIV is consistently lauded as an ideal diplomatic protector, a “bridle” against the territorial ambitions of William III (18). According to Switzerland, Holland has been enslaved to the absolute monarch Guillemot (30), an untenable situation that can only be remedied by purging itself of the poisonous “Orange juice” it had swallowed (32) and by forging an alliance with France (10, 13–15, 18, 21, 23, 36). In this way, the text seemingly reverses the attacks on Louis XIV’s ambitions for a “universal monarchy” and attempts to accuse other European sovereigns of that very aim (22).[17]

Yet the conversation shifts in a significant manner towards the end of this dialogue, with the general discussion of diplomacy turning towards a comparative analysis of monarchies and republics. After claiming that the French are both naturally predisposed and culturally conditioned to a form of submission that is incompatible within a republic (32–33),[18] Switzerland maintains that Holland’s most serious political mistake was allowing French exiles into its borders:

Ainsi ces serpents que tu as retirés et réchauffés dans ton sein, ont été des fléaux aussi funestes à ta liberté, qu’ils ont été utiles au Prince d’Orange pour la consommation de ses pratiques ambitieuses. Et si tu pouvais lire à nue dans tous les replis du coeur de ces réfugiés, tu verrais qu’il n’y en a pas un seul qui ne désire avec une passion violente de voir ton État Républicain détruit, et le Prince d’Orange souverain absolu de tes Provinces. (33–34)

Thus these serpents that you have secluded and warmed in your bosom, have been scourges as fatal to your freedom as they were helpful to the Prince of Orange for the consummation of his ambitious practices. And if you could see into the deepest recesses of these refugees’ hearts, you would see that there is not one of them who does not desire with a violent passion to see your Republican State destroyed, and the Prince of Orange absolute sovereign of your Provinces. (33–34)

Given that a republic’s “first” and “unique” goal should be the preservation of its freedom at any cost (9), the only “cure” to Holland’s enslavement to “Roi Guillemot” is to reclaim its lost liberty by expelling its “king” (45–46).[19]The use of a medical lexicon in these passages is significant (poison, remède, émétique, vomitif, intestins, médecin, purger, humeurs) (32), as it both underscores the severity of the disease (enslavement to an absolute monarch) as well as the urgent need for its remedy (purging the monarch).

In this respect, the interpolated fable allegorizing William’s ruse of the Dutch only heightens the subversive nature of this pamphlet. Although it conceals the attack within a second narrative layer, the fact that Switzerland gives the “key” to unlock the fable’s meaning to Holland before its told—(“tu as la clef de cette Fable avant que je te la dise”) (you have the key to this Fable before I tell it to you) (37)—encourages the reader to appreciate the parallels between the presentation of William as “renard rusé” and similar representations of Louis XIV as “renard rusé” in interpolated fables in other pamphlets from the same period.[20] More significantly, the inscription of the fable frames the need for revolt as a moral and even religious imperative, as seen in the following citation:

Ne sais-tu pas le vieux proverbe, Aide-toi & Dieu t’aidera: Est-il possible qu’entre tant de bons Républicains qui gémissent en secret de l’état auquel ils te voient réduit, pas un seul n’ait le courage d’animer les autres à rompre d’indignes liens. Ah brutes Brebis, esclaves d’un Renard, République réduite à la seule qualité de Trésorière de Guillemot, renvoie les Léopards dans leurs tanières, rappelles tes Dogues, & qu’une fois ils montrent les dents à ce ruse Renard. Laisse-le parmi ses Léopards démêler sa fusée, & rends-toi cette liberté si précieuse pour laquelle tu as répandu tant de sang, consommé tant d’armées, & souffert tant de travaux. (45, emphasis in original)

Do you not know the old proverb, Help thyself & God will help thee: Is it possible that among so many good Republicans who secretly lament the state to which they see you reduced, not one has the courage to motivate others to break unworthy ties. Oh crude Sheep, slaves of a Fox, Republic reduced to the sole occupation of Tiny Willy’s Treasurer, send back the Leopards to their dens, bring back your Mastiffs, and for once may they show their teeth to this cunning Fox. Leave him among his Leopards to clear up his business, & take back this precious freedom for which you have shed so much blood, consumed so many armies, & suffered so much hardship. (45, emphasis in original)

In positing an alternative to monarchyin the form of a lesson, this pasquinade indeed seems to shift from the satirical mode to a prescriptive call to arms— a rhetorical move signaled within the text not only by the accumulation of imperatives (renvoie, rappelles, rends-toi), but also by Holland’s “shocked” reaction to the moral: “Quoique ton discours m’ait un peu choquée, je ferai néanmoins de sérieuses réflexions sur tout ce que tu m’as dit” (Although your speech shocked me a bit, I will nevertheless reflect seriously about everything that you told me) (45–46). If the majority of the satire in La Pierre de touche politique functions due to the generalizability of the criticism of particular political leaders, it is through the glorification of republicanism that the texts are most strikingly transgressive. What is more, in engendering both shock and “serious reflections,” Le Noble’s pasquinades point to late seventeenth-century pamphlet literature’ssignificance as discursive spaces for critical inquiry—spaces in which readers are invited, and indeed encouraged, to dialogue with the text to move beyond “la superficie des choses” to arrive at “le fond essentiel” (La Fable 33).

IV. Conclusion(s): The Poetics and the Politics of Dissimulation under Louis XIV

Despite its inherent instability, the satirical mode is often described through the use of an archery lexicon: a given text “takes aim” at a given “target” by ridiculing the satirized object. According to this logic, late seventeenth-century Dutch and English pamphleteers “targeted” Louis XIV’s despotic aspirations for a universal monarchy, a charge against which the French crown retaliated by launching its own publicity war denouncing the tyranny of his political enemies. If this interpretation is conceptually useful, it masks the ways in which satire can operate in a more elastic manner, with the ridicule figuratively “ricocheting” between and among several disparate targets. Indeed, as we have seen through our analysis of Eustache Le Noble’s La Pierre de touche politique, it is perhaps this complexity that lends the satirical mode to evasively dodge the bullet of censorship. Unlike other examples of political pamphlets circulating at the turn of the eighteenth century, the pasquinades manipulate the divergent frames of reference of their readers, appealing effectively to two ideologically opposed audiences: the royal censors, thepasquinade’s immediate readers, and the general reading public.[21] As Pasquin suggests in Le Festin de Guillemot (1689),the question of point-of-view is paramount: “Par-là tu connaîtras facilement qu’il est bien aisé de se tromper, & de prendre des vessies pour des lanternes lorsqu’on a la vue mauvaise, & qu’on se sert de Lunettes fausses” (By this you will easily understand that is very easy to make mistakes, & to get the wool pulled over one’s eyes, when one has poor vision & uses false Glasses)(43–44). By exploiting precisely the monarchy’s “poor sight” and “false glasses,” Le Noble managed to publish texts that denounce absolutism and laud the emancipatory potential of republics. It is perhaps this utility that Le Noble claims his texts will hold for “les Historiens futurs” in the preface to Le Cibisme.

In addition to their political and historical importance as examples of early modern propaganda and proto-journalistic rapportages, however, the pasquinades’ literary features are equally critical. Despite their discursive complexity, we have seen that the pamphlets often announce the narrative game that they are playing, inscribing the key to their political significance into the fabric of the text. In the same way that the aforementioned evocation of “skewed vision” and “surface-level” reading renders the dialogues’ subversive contents more easily decipherable, these metaleptic moments throughout the Pierre de touche politique collection clarify their textual construction as they contribute to their literary complexity. Holland’s response to Switzerland’s wisdom in La Fable du Renard is again revelatory. At the close of the pamphlet, Holland summarizes the consequence of his dialogue with Switzerland in terms that recapitulate the general interest of the dialogic function in the pasquinades: “Tu m’ouvres les yeux sur des choses auxquelles je n’aurais jamais pensé, et cependant je m’aperçois bien de la vérité de ton raisonnement” (You are opening my eyes to things about which I never would have thought, and yet I clearly perceive the truth in your reasoning)(34–35). Indeed, the relevance of thePierre de touche politique pamphlets at the dawn of the French Enlightenment resides in this incessant vacillation between interlocutor and reader, between historical fact and authorial invention, and between monarchical praise and monarchical denunciation. Even as they playfully “banter” about current events (La Bibliothèque 3), The Political Touchstone pamphlets theorize republicanism and encourage readers to question blind submission to authority, employing an early enlightenment-style reader manipulation that fosters critical inquiry. Rather than dismissing these texts as propaganda spreading “lies” to a passive, gullible audience, I would like to suggest they be considered as active in constructing new frameworks for debates (Onnekink 150).[22] In addition to “shocking” readers, the Pierre de touche politique dialogues analyze the distinctions between monarchy and despotism, between traditional and“absolute monarchies, and between monarchies and republics. They invite the reader into a discursive space of critical inquiry even as they attempt to construct “new interpretative frameworks” for that space. They function collectively as ekphrastic machines, transporting readers into the chaos of the past and resurrecting history before our own eyes. Most importantly, they show us that Enlightenment, cognitive or cultural, does not emerge from a vacuum, but surfaces slowly as a product of dialogic exchange. Le Noble’s pasquinades merit further consideration by contemporary scholars precisely because, as Pasquin puts it, whoever dislikes these “harmless divertissements” is not a “Français,” but a “franc-sot” (Le Festin 43–44).

New York University

Works Cited

Bak, János M., ed. Coronations: Medieval and Early Modern Monarchic Ritual. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

Bodin, Jean. Les six livres de la république. Geneva: C. Le Jung, 1577.

Bonnet, Pierre, ed. Littérature de contestation : pamphlets et polémiques du règne de Louis XIV aux Lumières. Paris : Editions le Manuscrit, 2011.

Cherbuliez, Juliette. “The Outlaw’s Itinerary: Identity and Circulation in Eustache Le Noble’s La Fausse Comtesse d’Isamberg.” The French Review 73.3 (Feb 2000): 475–485.

Collinet, Jean-Piere, Philippe Hourcade, and François Moureau. “Eustache Le Noble.”Dictionnaire des Journalistes, 1600–1789. Ed. Jean Sgard. Vol. 2. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1999. 625–628.

Funck-Brentano, Franz. Les Lettres de cachet à Paris: Étude suivie d’une liste des prisonniers de la Bastille (1659–1789). Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1903.

Godenne, René. Préface. Ildegerte, reyne de Norvège : ou L’amour magnanime. By Eustache Le Noble. Genève : Skatline Reprints, 1980. I–XVIII.

“Historical Bibliography: Eustache Le Noble.” Notes and Queries: A Medium for Intercommunication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc. Vol 5. London: George Bell, 1852. 52–54.

Harrison, Helen L. “The Follies of Notre Bon Homme, or How to Lampoon a Hope while Praising the Eldest Son of the Church: the 1688 and 1689 Pasquinades of Eustache Le Noble.” College of William and Mary. Williamsburg, Va. 28 Oct. 2004. Conference Paper.

Horace. Satires, Book 1. Ed. Emily Gowers. Cambridge, Eng.: Cambridge UP, 2012.

Hourcade, Philippe. Entre pic et rétif: Eustache Le Noble (1643–1711). Paris: Amateurs de livres, 1988.

Israel, Jonathan I. The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness and Fall, 1477–1806. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1995.

Klaits, Joseph. Printed propaganda under Louis XIV: absolute monarchy and public opinion. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1976.

Koebner, Richard. “Despot and Despotism: Vicissitudes of a Political Term.” Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 14 (1951): 275–302.

Le Noble, Eustache. La Bibliothèque du roi Guillemot : sixième dialogue. London: Chez Jean Benn, 1690.

———. La Chambre des comptes d’Innocent XI : dialogue entre Saint-Pierre & le Pape à la porte du paradis. Rome: Chez Francophile Aletophile, 1689.

———. La Diète d'Ausbourg ou La guerre de l’aigle et du coq : huitième dialogue. Vienna: Chez Peter Hansgood, 1690.

———. La Fable du renard : septième dialogue, entre la Suisse et la Hollande. Leyde : Chez William Newking, 1690.

———. Le Cibisme : Entre Pasquin & Marforio, sur les Affaires des Temps. Rome: Chez Francophile Alethophile, 1691.

———. Le Couronnement de Guillemot et de Guillemette : troisième dialogue entre Pasquin & Marforio sur les affaires du temps ; avec le sermon du grand Docteur Burnet. London : Chez Jean Benn, 1689.

———. Le Festin de Guillemot : quatrième dialogue de Pasquin & de Marforio. London : Chez Jean Benn, 1689.

Les soupirs de la France esclave qui aspire après la liberté. N.p.: n.p., 1689.

Onnekink, David. “The Revolution in Dutch Foreign Policy (1688).” Pamphlets and Politics in the Dutch Republic. Ed. Femke Deen, David Onnekink and Michael Reinders. Leiden: Brill, 2011. 143–172.

Mangeot, Stéphane. “Eustache Le Noble, procureur général au parlement de Metz (1672–1682): Aventurier et homme de lettres.” Mémoires de l’Académie nationale de Metz.Vol. 15. 55–83. Metz: Editions le Lorrain, 1934.

Martin, Henri-Jean. Livre, pouvoirs et société à Paris au XVII siècle (1598–1701). Vol. 2.Genève: Droz, 1969.

Michaud, Joseph F. and Louis G. Michaud. “Eustache LeNoble.” Biographie universelle, ancienne et moderne, ou Histoire par ordre alphabétique de la vie publique et privée de tous les homes qui se sont fait remarquer par leurs écrits, leurs actions, leurs talents, leurs vertus ou leurs crimes: ouvrage entièrement neuf. Vol. 24. Paris : Michaud frères, 1811–1862. 85 vols. 93–95.

Örsy, L.M. “Conciliarism: Theological Aspect.” New Catholic Encyclopedia. 2nd ed. Ed. Marthaler, et al. Vol. 4.New York: Thomas Gale, 2003. 15 Vols.

Ott, Michael. “Pope Innocent XI.” Catholic Encyclopedia. Ed. Herbermann, et al. Vol. 8.New York: The Encyclopedia Press, 1910. 15 Vols.

“Pasquin.” Encyclopédie, ou dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, etc. Eds. Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond D’Alembert. University of Chicago: ARTFL Encyclopédie Project (Spring 2011 Edition). Ed. Robert Morrissey. http://encyclopedie.uchicago.edu/. Web.

“Pasquinade.” Dictionnaire universel, contenant généralement tous les mots françois tant vieux que modernes, et les termes de toutes les sciences et des arts. By Antoine Furetière. LaHaye et Rotterdam : A. & R. Leers,1690.

Ravaisson, François. Archives de la Bastille: Documents inédits recueillis et publiés. Vol. 8. Paris: A. Durand et Pedone-Lauriel, 1876.

Reynie, Gabriel Nicolas de la. “Lettre du 5 août 1694.” Bibliothèque nationale, Papiers Harlay, 679.

Richter, Melvin. “Despotism.” Dictionary of the History of Ideas: Studies of Selected Pivotal Ideas. Ed. Philip Wiener. Vol. 2. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1973.

Rosen, Ralph M. Making Mockery: The Poetics of Ancient Satire. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Seifert, Lewis C. Fairy Tales, Sexuality, and Gender in France, 1690–1715: nostalgic utopias. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Smith, Jay M. Nobility Reimagined: The Patriotic Nation in Eighteenth-Century France. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005. Print.

Tierney, B. “Conciliarism: History of.” New Catholic Encyclopedia. 2nd ed. Ed. Marthaler, et al. Vol. 4.New York: Thomas Gale, 2003. 15 Vols.

[1] Given Le Noble’s reputation, it is unclear how this relationship was forged. The publication of Charenton, ou l’Hérésie détruite (1686), which praised the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, may have earned Le Noble the graces of Madame de Maintenon, a relationship that he only solidified by dedicating his Traduction nouvelle en vers des Pseaumes de David to her in 1692 (Hourcade 52). Le Noble may have benefited from other protectors in high places, such as French magistrate Toussaint Rose, reportedly a friend of Le Noble’s father, as well as the lieutenant-general of police Marc-René de Voyer de Paulmy d’Argenson, who provided a small weekly allowance to Le Noble at the end of his life (116). Some have suggested that Le Noble was a distant relative of Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs Charles Colbert de Croissy. However, the fact remains that the degree of his protection was inconsistent, as some of his texts were authorized while others condemned or seized. See Hourcade (115–120) for several hypotheses regarding these “Approbations et protections masquées.”

[2]He was imprisoned at three different junctures: in the Bastille and For-l’Évêque prisons from 1683–1684 for having forged signatures to swindle his creditors; in the Châtelet and the Conciergerie prisons from 1690–1695 for having falsified documentation pertaining to the inheritance of territories; and in the Conciergerie from 1703–1704 for adultery (Hourcade 45–66; Godenne VIII; Funck-Brentano 73; Ravaisson 246–247). Le Noble escaped from prison in 1695 and lived in hiding with his mistress, Marie-Gabrielle Perreau, until their capture in 1697. Although he had been banished in 1693—a sentence which was reaffirmed in 1697—Le Noble was nevertheless allowed to live discreetly in Paris (Hourcade 60). My study relies heavily on Philippe Hourcade’s monograph Entre pic et rétif : Eustache Le Noble (1643–1711), to date the only comprehensive critical study of Le Noble’s oeuvre. Unless otherwise noted, all biographical references are taken from Hourcade’s work.

[3] Although best known as the author of the pasquinades, Le Noble published in nearly every literary genre, penning historical novellas, psalm-paraphrases, astrological treatises, theatre, fairy tales, poetry, treatises on religious doctrine, and fables. His Oeuvres complètes appeared in 19 volumes between 1718 and 1726, and his works were translated into English, German, and Italian. See Hourcade (150–152) for a chronological bibliography of Le Noble’s works.

[4]Le Noble’s works have typically been featured within general studies (see Seifert) and have usually attracted attention on ideological grounds (see Martin). Recent scholarship, however, has emphasized both the literary interest of his novels as well as their potential influence on eighteenth-century works such as Manon Lescaut (see Cherbuliez). Philippe Hourcade’s exhaustive study draws upon meticulous archival research, but it is first and foremost a work of literary history that overlooks the subversive political content of Le Noble’s pasquinades.

[5]Le Noble published five collections of pasquinades, the titles of which are listed below: La Pierre de touche politique ou dialogues sur les affaires du temps (29 dialogues; 1688–1691), La Fable du rossignol et du coucou (1 dialogue; 1692), Les Travaux d’Hercule (21 dialogues; 1693–1694), L’Esprit d’Esope (4 dialogues; 1694), and Nouveaux Entretiens politiques (87 dialogues; 1702–1709). While his name did not appear on the manuscripts of the pasquinades, Le Noble was presumed to have been their author by his contemporaries and his engraving appeared with these works.

[6] Hourcade has noted that Le Noble’s ambition to write “un Essai Historique” (Le Cibisme 4) belies an attempt to compete with the periodical Le Mercure historique et politique (227).

[7]As Michael Ott writes, “The whole pontificate of Innocent XI is marked by a continuous struggle with the absolutism of King Louis XIV of France” (21). In 1687, Louis XIV seized papal territory, imprisoned the papal nuncio, and threatened to separate France from the Roman Catholic Church in response to papal decisions with which he disagreed, prompting his excommunication by the pope (Ott 21–22).

William III, Prince of Orange became the Stadtholder, or provincial governor, of the provinces of Holland, Zeeland, and Utrecht in 1672. Preoccupied with strengthening the power of the United Provinces against France, which had invaded the Dutch Republic in 1672, William of Orange aspired to the British crown to establish “an anti-French, and anti-Catholic, parliamentary monarchy” (Israel 849). Dutch forces invaded England in November 1688, and William deposed his uncle and father-in-law, James II, in December of the same year, officially becoming joint sovereign of England, Scotland, and Ireland with his wife Mary II in February 1689 (849–852).

[8]Each pasquinade was published with its own clever, original title. Le Noble explains the rationale behind his first pamphlet’s title in these terms: “[je l’ai] nommé Cibisme, parce que le Népotisme ayant été proscrit sous le Pontificat d’Innocent XI le Cardinal Cibo y a tenu la place de neveu & de premier ministre” ([I named it] Cibisme because Nepotism having been proscribed under the Pontificate of Innocent XI Cardinal Cibo assumed the rank of nephew and prime minister) (Cibisme 4). The pope’s decision to side with William of Orange (a Protestant) in the War of the Grand Alliance is most notably denounced in La Chambre des comptes d’Innocent XI, in which Innocent XI must answer to Saint Peter for his crimes against the Church.

[9]Hourcade has suggested that the controversial nature of Le Noble’s political dialogues explains their complicated publication history, as well as the government’s ambiguous role in approving them, if only tacitly. Some government officials saw in the pasquinades an opportunity to garner support for State policy, while others feared explicitly approving the dialogues’ ridicule of European leaders. On several occasions the approval of the pasquinades was superficially revoked only to be promptly reinstated by royal authority (Hourcade 108–112). In Livre, pouvoirs et société à Paris au XVIIe siècle, Henri-Jean Martin maintains that the French crown clandestinely supported Le Noble’s pasquinades to increase support for the war against the League of Augsburg (669–670; 899–900). Others have speculated that Le Noble was hired as a propagandist by British Jacobites, those who sought the restoration of James II. In the January 1852 edition of the scholarly journal “Notes and Queries,” for instance, the anonymous author argues that the deposed King of England James II may have partially financed Le Noble’s Pierre de touche dialogues in order to turn public opinion against William of Orange, who had forced his abdication (5: 52–54). See also Harrison’s unpublished conference paper “The Follies of Notre Bon Homme,” which I have listed in the Works Cited.

[10]The fifteen “mémoires” composing Les Soupirs de la France esclave, qui aspire après la liberté were originally published anonymously, but have been attributed to Pierre Jurieu and Michel Le Vassor. Antony McKenna has questioned both attributions in a chapter published within Pierre Bonnet’s edited volume Littérature de contestation : pamphlets et polémiques du règne de Louis XIV aux Lumières (2011).

[11]The Latin citation combines Psalms 2:4 and 36:10 from the Bible.

[12]The sixteenth-century religious wars produced a rich body of pamphlets that accuse the monarchy of tyranny in the aftermath of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in 1572. The Vindiciae Contra Tyrannos: or, concerning the legitimate power of a prince over the people, and of the people over a prince (1579), for instance, charges the French crown with having degenerated into tyranny and contends that subjects have the right to resist a king who disobeys the laws of God— arguments that would resurge in the second half of the seventeenth century after the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685. My dissertation focuses on anti-monarchical pamphlet literature from the late seventeenth century, but highlights the extent to which these works draw on tropes from previous generations of libelles and indeed increase their rhetorical force through the imitation of lieux communs deployed in preceding texts.

[13] In Coronations: Medieval and Early Modern Monarchic Ritual, Bak acknowledges William III’s effective use of spectacle to strengthen his political authority: “Macaulay wrote ‘If pageantry is to be of any use in politics, it is of use as a means of striking the imagination of the multitude.’ The Stuarts never grasped this essential principle of modern politics, but their successor did: William III set out to dazzle the citizens of London with a magnificent and carefully planned progress in order to enhance his shaky claims to the throne” (225). For more on this topic, see Lois G. Schwoerer ‘The Glorious Revolution as Spectacle: A New Perspective’ in England’s Rise to Greatness, 1660–1763 ed. Stephen B. Baxter (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 1983) 109–149; and ‘Propaganda in the Revolution of 1688–89’ The American Historical Review 82 (1977): 843–874.

[14]La Pierre de touche politique dialogues differ, however from the works of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century political theorists, which separately analyze tyrannical, traditional, and despotic monarchies. For example, Jean Bodin separately treats tyrannical, royal, and despotic monarchies in his Six Books of the Commonwealth (1576). Although the semantic equivalence of tyranny and despotism in Le Noble’s political dialogues differs from Bodin’s treatment of despotism within the specific context of conquered territories, it remains that the pasquinades often consider the subtleties of different forms of government in the manner of political theory.

[15]The semantic resonances of the word “despotic” have been well documented by historians. Initially deployed in France to criticize the perceived threat posed by the concentration of the crown’s political power at the time of the Fronde, the term “despotic” assumed an even more pejorative connotation by the final years of the seventeenth century, evoking a system once associated with the Turks in which subjects of an absolute monarch were rendered slaves to a despot through their dependence on the impulses of the self-interested monarch (Koebner 299; Smith 28–29). Koebner has argued that this criticism reached a high point during the late 1680s, the period during which Le Noble was drafting his Pierre de touche politique pamphlets: “Louis by the onslaught on the Palatinate had opened his most high-handed war in the winter 1688–89. This war was certain to expose France to the enmity of all Europe; it was certain to jeopardize the economic recovery of the country, already made precarious by the exodus of so many Huguenots. Such national dangers were, it appeared, incurred only to satisfy the boundless personal ambition of the king” (297).

[16]For further information on libels written against Louis XIV, see Van Malssen’s seminal study Louis XIV d'après les pamphlets répandus en Hollande (A. Nizet & M. Bastard 1936) or Schillinger’s more recent monograph Les Pamphlétaires allemands et la France de Louis XIV (Peter Lang 1999). Hans Bots’s article “L'écho de la Révocation de l’Edit de Nantes dans les Provinces Unies à travers les gazettes et les pamphlets” analyzes in particular the pamphlets written in the aftermath of the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The collection Espaces de la controverse au seuil des Lumières (1680–1715), published in 2010, explores the polemical battles incited in the theological, political, literary, and scientific domains in Europe during the “crise de la conscience européenne.” Clandestine publications and pamphlet literature were the focal point of a 2009 colloquium in Tours, France, the contributions of which were published under the title Littérature de contestation: Pamphlets et polémiques du règne de Louis XIV aux Lumières. My dissertation will consider in detail the fascinating complexity of the intertextual relationships between Eustache Le Noble’s pasquinades and contemporary political pamphlets.

[17]See Burnard’s “Les pamphlets contre la politique belliciste de Louis XIV” for a succinct analysis of pamphlets denouncing Louis XIV’s territorial ambitions.

[18]The notion that the exiled French refugees were born with a “proposition naturelle à l’État Monarchique” (natural inclination for the Monarchical State) (33) is also related to other passages which draw on the Aristotelian notion, later developed by Bodin, that the form of government corresponds to a country’s natural geography (8–9).

[19]In a similar fashion, critics of Louis XIV’s absolutism insisted on the fact that the French monarchy was elective in order to justify the people’s right to depose the king. See Les Soupirs de la France esclave, especially the Sixth Memoir (79–94): “Il est indubitable que ceux qui pouvoir d’élire, ont aussi celui de déposer” (It is irrefutable that those who have the power to elect also have the power to depose) (84).

[20]See especially the anonymous publication L’Esprit de la France et les maximes de Louis XIV découvertes à l’Europe (Cologne: Pierre Marteau, 1688).

[21]Further research is needed to hypothesize about the precise readers of the pasquinades. As previously mentioned, Klaits insists upon the “wide readership” of Le Noble’s pamphlets (146), but their publication history complicates these questions of circulation.

Interestingly, there are several intratextual references to the translation and censorship of the Pierre de touche politique dialogues. In La Fable du renard, for instance, Holland states: “Si je savais qui est l’impertinent qui s’amuse à me traiter de la sorte, je m’en plaindrais à mon Statoûder, qui par Arrêt de son Parlement le ferait pilorier comme on a fait le Chapelain de l’Evêque de Durham pour avoir traduit en Anglais cette misérable pièce intitulé le Couronnement de Guillemot, où le Sermon du saint homme & bon Apôtre le Docteur Burnet est si sottement tourné en ridicule” (If I knew the impertinent one who amuses himself by treating me this way, I would complain about it to my Stadtholder, who by Arrest of his Parlement would have it pilloried like one did the Bishop of Durham’s Chaplain for having translated into English this pathetic piece entitled the Coronation of Tiny Will, where the Sermon of the saintly man and good Apostle the Doctor Burnet is so foolishly derided) (42, emphasis added). Likewise, the exchange between Marforio and Pasquin at the close of Le Festin de Guillemot references the censorship of the pasquinades.

[22]Here, Onnekink draws upon Sheryl Tuttle Ross’s analysis of propaganda as “epistemically defective,” in that its message cannot be authoritatively verified or refuted, in order to comment upon the early modern Dutch pamphlet tradition (150).

As reflected in my Works Cited, there is a great deal of recent historical scholarship on the role of pamphlets in spreading political and religious heterodoxy in France and in a larger European context.