“Erection,” in Flaubert’s Dictionnaire des idées reçues, should only be said in reference to monuments. It might feel as if “election,” in recent times, risks a similar fate, as a word not to be brought up in polite society. Let’s not let that happen. To that end, here’s to talking about elections, with early modern-infused takes on public opinion (Michael Meere), political insult (Kathrina LaPorta), femmes fortes (Chloé Hogg), and the matter of media (Christophe Schuwey). – CH

On Technology and Public Opinion

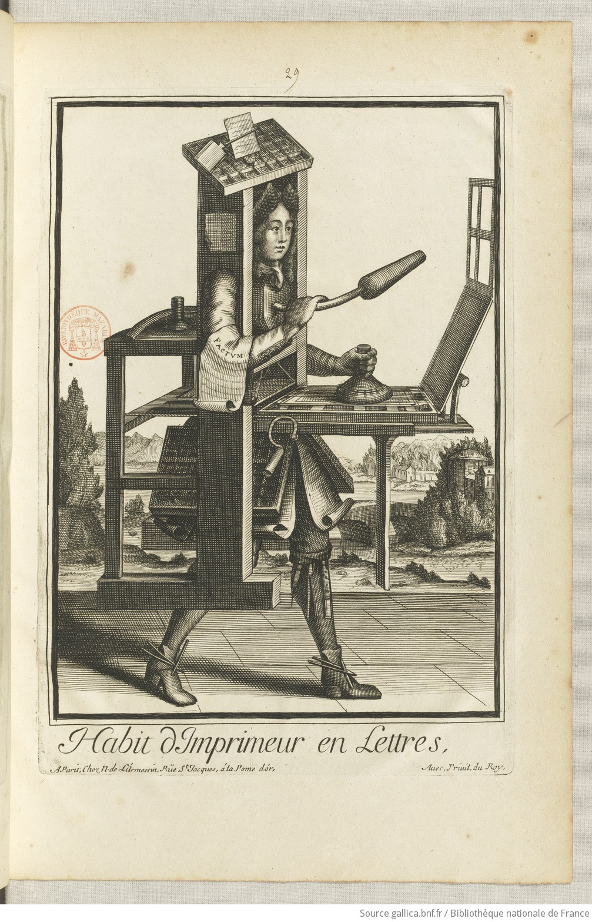

Fig. 1. Plate from “Habit d’imprimeur en lettres.” Nicolas II de Larmessin, Costumes grotesques, 1695.

The ubiquity of pocket-computers and the mental image of social media users on their devices, creating content as they walk, reminds me of the playfully allegorical engraving by Nicolas II de Larmessin (1632-1694), “Habit d’imprimeur en lettres,” the 29th plate in the Costumes grotesques collection (completed and printed posthumously in Paris in 1695 by his brother and nephew, Nicolas III and Nicolas IV de Larmessin). The ambulating printer inks the text in the bed of the press with a beater in his left hand and holds the base of the lever, or devil’s tail, with his right hand. It is also noteworthy that the man and the machine appear to be fused together, as the platen makes the impression on the paper inside the man’s own abdomen. The bionic printer then brandishes on his right arm the only folio with legible type, FACTUM, a provocatively ambiguous title intimating the potential polemical and libelous undertones of the printing press technology at that time, just as in ours we face the increasingly menacing and unpredictable powers of twenty-first-century technologies to misconstrue facts and deform reality for personal or political gain.

Indeed, the more I learn about how echo chambers and epistemic bubbles – driven not only by social media’s algorithmic recommender systems and filter bubbles, but also older forms of media such as radio, television, and print – might have affected the outcome of the US presidential election (as well as elections around the world, 2024 being dubbed by Time magazine as “the ultimate election year” with elections held in over 60 countries), I can’t help but think about the impacts of the printing press on public opinion in early modern France. While some authors did claim to want to change people’s minds, especially during Louis XIV’s long reign, much of the propaganda produced during the wars of Religion, the rise of Louis XIII, or the Fronde was rarely intended to persuade anyone about the legitimacy (or illegitimacy) of, say, the assassination of the Duke of Guise and his brother Louis at Blois in 1588, or the Siege of La Rochelle in 1627-1628. Rather, many of the countless texts and images, printed en masse and circulated throughout the French Kingdom thanks to this relatively new technology, tended to reinforce already established belief systems and, if necessary, to “enflame the base,” so to speak. Sometimes, and though it is difficult to measure, these virulent and highly charged representations could spark rebellion, revolt, and violence, not unlike the ways in which the rhetoric spouted by leading media and political figures has been linked to the incitement of the storming of the US Capitol on January 6, 2021… How might future election cycles play out, I find myself wondering, if (or perhaps when) we, current-day reincarnations of Larmessin’s man in the printing press, are supplanted by AGI robots?

Michael Meere, Wesleyan University

***

On Tyranny and/as Political Insult, or Not Another Election Post-Mortem

What’s in a name? The recent accusations that Donald Trump has tyrannical tendencies echo similar charges levelled against the French absolute monarch, Louis XIV. Following the Sun King’s Revocation of the Edict of Nantes in October 1685, which ushered in a new era of religious violence against French Huguenots, pamphleteers from across Europe sounded the warning bell against what they deemed the king’s desires to reign as a tyrant –– or worse yet, as a despot –– over his subjects. While “tyrant” and “despot” were often used interchangeably, the latter term possessed a particularly damning valence for the so-called “Most Christian King.” Associated with the Ottoman Empire, the word “despot” conjured imagery of a populace virtually enslaved to their ruler, whose arbitrary whims governed the country in an inhumane, un-Christian manner. No wonder one of the architects of absolutist ideology, Pierre Bossuet, took pains to distinguish absolutism from the arbitrary style of governance associated with tyrants and despots. In his Politique tirée des propres paroles de l’Écriture sainte from 1709, Bossuet writes: “Pour rendre ce terme [de monarchie absolue] odieux et insupportable, plusieurs affectent de confondre le gouvernement absolu, et le gouvernement arbitraire” (In order to make this term [absolute monarch] odious and insupportable, many pretend to confuse absolute government and arbitrary government). The term “odieux” (odious) would have carried an especially potent affective charge for a late seventeenth-century public: the 1694 entry in the Dictionnaire de l’Académie Française insists upon the adjective’s power to incite feelings such as aversion, hatred, and indignation.

It seems that a similarly powerful affective response was sought in the leadup to the 2024 election in the United States. Although Democratic messaging vacillated between Joe Biden’s and Kamala Harris’s respective candidacies (and fluctuated even in the final weeks of Harris’s run), the party placed a lot of hope and ad money in the apparently misguided belief that Americans would be terrified –– if not repulsed –– by Donald Trump’s desire to rule as a fascist-dictator-tyrant, abolishing all of the norms and pillars of American democracy in the process. Countless interviews, speeches, articles, and even entire books have centered on the risks of Trumpian authoritarianism, as well as the accuracy of each term (is he a tyrant, a dictator, a full-blown fascist, or nothing of the sort?), as though the objective of Democratic electoral strategy was to produce a political philosophy textbook on types of authoritarianism. Much was also made of Harris’s decision to use the “f-word” in the final weeks before the election, conjuring the nightmare of World War II and with it, perhaps, as much affective freight as the “d-word” would have evoked for a seventeenth-century French public.

What’s been overlooked in these discussions are the different success rates behind the different types of “name-calling” used by Democrats and Republicans, respectively. While Dems denounced Trump’s tyrannical leanings, the GOP gained traction with voters by mocking Harris for her “woke” cultural policies. What should we make of these labels and, gesturing to speech-act theory, how might we understand their perlocutionary power?

The goals of associating Trump to various types of authoritarianism were likely similar to those used by pamphlet writers desperate to protect French subjects from persecution and usher in reform of the monarchy before it was too late. Calling Louis XIV a tyrannical despot and Donald Trump an authoritarian fascist are insults. By using these labels, and yes, even applying them in a non-rigorous manner, opponents to both leaders were attempting to incite fear to bring about change. In speech-act terms, the words were meant to have a perlocutionary effect, bringing about an emotional response and a change in behavior. In other words, the tyranny accusation and the “fascism thesis” are less about accuracy and more about their political valence.

But an insult is only as good as its ability to echo and reverberate through public spaces. While the despotism label caught on among dissenters in the final decades of the 1600s, Louis XIV did not heed calls to reform his policies (and his subjects were powerless to reform the monarchy, until, of course, future generations took matters into their own hands in 1789). As we all know by now, polling shows that neither the dictator nor the fascist labels swayed droves of voters against the Republican nominee; one ABC News/Ipsos poll even found that approximately 20% of registered voters believed that Harris met the definition of fascist.

The label “woke,” on the other hand, overperformed: an umbrella term with little clear meaning, “woke” –– alternately associated with social justice programs, the attempt to police speech, or the equally nebulous “cancel culture” –– seems to have been successfully imposed on the entire Democratic Party, with Harris as the wanna-be-woke-commander-in-chief. As is the case with the tyranny accusation, accuracy is less important than efficacy: the mere suggestion that Harris would follow a “woke” agenda” found purchase among swing voters, as suggested by the highly effective pro-Trump ad stating that Haris was with “they/them” while the former president would advocate for “you.” Meanwhile, the so-called champions of free speech have been advocating for book bans in American schools and criminal charges against librarians who do not remove this (cancelled) content from bookshelves, approximately 40% of which treat LGTBQ+ themes or feature characters of color. Censorship, it would seem, is a perfectly acceptable tool to defend freedom of speech against wokism so long as you are targeting woke material.

TL;DR: in the battle of 21st-century political insults, woke trumps tyranny.

Kathrina LaPorta, New York University

***

Femmes fortes Existing in Context

Fig. 2. Kamala Harris Attack of the Competent Woman Meme. Tumblr.

Fig. 3. “Jaël.” Illustration from Pierre Le Moyne, La Gallerie des femmes fortes, 1647.

Turn the pages of Pierre Le Moyne’s Gallerie des femmes fortes (1647), and the women leap off the paper, each one gloriously large, overpowering the visual field and filling up the foreground. Jaël strides with her hammer and spike, Judith brandishes Holofernes’s head (held tidily with a cloth underneath), and an armored, be-plumed Zénobie wields her spear. Behind each woman, something’s going on, but it’s hard to see the tiny figures there that play out scenes of death and mayhem. The optical adjustment needed to shift focus from the aggressively foregrounded women to the diminutive background gives one’s eyes a workout, reminding us that looking at women leaders takes an effort—it’s not necessarily a sight we’re trained to see.

I’m at a book exhibit in the University of Chicago Special Collections, organized for the SE17 conference last October. I’ve only ever seen the femmes fortes before in reproduction—the first time, in the pages of Joan DeJean’s Tender Geographies. The effect of seeing the illustrations in person, on the page, is gasp-out-loud vivid—the women are so supersized, so crisply engraved by Gilles Rousselet, set against the background scenes etched by Abraham Bosse, that’s it’s like viewing in 17th-century technicolor. Tiny busy figures doing things in the background give the effect of a scrolling diorama of action, context, lore. I’ve seen this image more recently, I realize, a supersized woman, at once glorious and menacing, bursting through a visual field. It’s the meme of Kamala Harris as Attack of the Competent Woman, itself a mash-up of the poster for the 1958 cult horror-sci-fi flick, The Attack of the 50 Foot Woman. The image features Vice President Harris in her signature suit, pearls, and dazzling smile, gigantified, holding a tiny flailing man in her hand (is that Trump?) and creating havoc in a mid 20th-century urban carscape. The meme is funny, complimentary, but seeing it shared all over Bluesky, I have wondered, why does the first Black woman, the first Asian-American woman, the first woman to be president (November 6th hasn’t hit yet) have to be depicted as a scary giant? Indeed, how close is this image to what Cecilia Cerja, Nicole Nave, Kelly Winfrey, Catherine Helen Palczewski and Leslie Hahner call (after Caitlin Bruce) the “toxic archive” of digital misogynoir targeting Harris?

A woman leader, then, as mediated by the meme of a Giant Competent Harris or the illustration of a supersized femme forte, is visually out of whack. She is too big for her context. Yet it’s context that took center stage in the early days of the Harris campaign, in the exuberant meming of the exhortation VP Harris received from her mother, Dr. Shyamala Gopalan, “You exist in the context of all in which you live and what came before you.” And it’s context, the visual background against which each femme forte asserts her glory, which as Derval Conroy argues, Le Moyne spent the bulk of the text of La Gallerie des femmes fortes “explaining, describing, narrating,” on behalf of the readers whose reactions he seeks to shape. As much of the post-election processing devolved into accusations of not getting the proportions right (too many celebrities! not enough podcasts!), what we seemed to miss sight of was what Harris told us to attend to: our contexts.

Chloé Hogg, University of Pittsburgh

***

Se frotter à la matière

“Medium is the Message.” Avant comme après l’élection de 2024, l’analyste politique Dan Pfeiffer a souligné, avec sa qualité d’analyse habituelle, le rôle absolument crucial des médias. Non pas simplement « les » médias au sens traditionnel du terme, mais bien la diversité des supports de communication, et leur capacité à être vus et entendus: qu’importent les faits et les statistiques, l’élection a été remportée par le parti capable de marteler sa vision, ses présupposés et sa marque auprès du plus grand nombre, et à toucher celles et ceux qui, précisément, ne suivent pas « les » médias.

En tant que dix-septièmistes, nous travaillons sur un corpus d’ouvrages qui ont cherché cette efficacité, transformé les publics cibles, réinventé la communication royale. Prenons le cas de l’infotainement toxique à la Fox News. Avant même le Mercure galant, Edmé Boursault insère dans un roman galant apparemment anodin des récits entiers de la Guerre de Dévolution, jouant sur la limite entre faits et fiction. Les éléments de langage sont si outranciers – la ville soulagée d’être conquise, au point de regretter même sa résistance – que certaines propagandes contemporaines n'oseraient faire pareil. Mais, subtilement distillés dans une fiction plaisante, ils séduisent, passent tout seuls, comme une hallucination collective. Que l’on pense également aux faux débats sur un plateau de télévision, dans lesquels les invités sont, en réalité, acquis à la même cause. Bien des « conversations » mises en scène dans les récits du XVIIe siècle relèvent de la même technique. Quant à l’expression « Fake News », qui discrédite toute information incommodante et tout média contradictoire, on rappellera que Molière a profité du mégaphone qu’est le théâtre pour ridiculiser à la fois toute gazette étrangère, et toute personne ayant la prétention de s’intéresser aux affaires d’État.

Parfois, la littérature incarne la résistance. Mais il y a aussi toute une production littéraire qui travaille vers le pouvoir, s’affairant à démontrer sa capacité à imposer directement le message royal en échange de gratification. Dans ces écrits-là, il n’y a pas de résistance, mais une sophistication médiatique cynique et manipulatoire pour gagner la guerre de l’opinion. Difficile d’accepter ce rôle de la littérature: il faudrait, dit-on, sauver le Grand Siècle. N’est-ce pas pourtant précisément parce qu’ils nous permettent aussi d'analyser ces pratiques et ces techniques à un moment critique — l’aube de la sphère publique — qu’il est primordial d’étudier les écrits de notre siècle? N’est-ce pas une analyse littéraire de premier ordre que de décrypter le lien subtil entre médias et littérature, de réfléchir aux moyens de toucher, d’être efficace, en rapport avec des questions concrètes de segmentation des publics et de circulation?

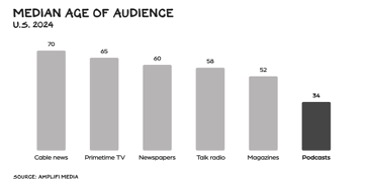

Passer du traité historiographique au roman propagandiste ne va pas de soi; aujourd’hui, passer de la télévision au podcast non plus: c’est un style, un savoir-faire, une transformation qui engage tout le contenu. Cette difficulté à penser le support et sa diffusion comme partie intégrante du message m’invite ainsi à une double réflexion pour la littérature. Une évolution interprétative, d’abord: il est désormais fondamental, sous peine de maintenir une illusion critique et politique, d’intégrer les différentes dimensions des médias et de la matérialité à nos analyses. La sociologie des textes l'a dit depuis longtemps : il n’y a pas de texte écrit hors de la matérialité, de sa circulation, de ses appropriations, donc, les conditions matérielles déterminent le texte. Il n’y a pas de sens immanent du texte, il faut montrer comment le sens que l'on donne au texte a pu circuler, être reçu, par la diversité des publics.

Un appel à intervenir, ensuite: nous, spécialistes de la première modernité, devrions prendre part aux réflexions contemporaines sur ces phénomènes; au moins autant que les historiens, les sociologues ou les spécialistes des médias l'ont fait dans les dernières années. Les élections se sont jouées sur des questions de narration, d’attention, de rhétorique – mais d’une rhétorique adaptée au médium –, de public, d’émotions et de fictions: autant de sujets dont les études littéraires sont expertes. Nous avons les outils théoriques et le recul pour analyser ce qui se passe et sortir d’un présentéisme stérile... à condition, bien sûr, de ne pas assigner la littérature du côté des gentils, et de ne pas la réduire à une stricte fonction esthético-philosophique. Plusieurs ouvrages et articles ont montré la voie dans les dernières années: menons cette lutte au premier plan.

Christophe Schuwey, Université Bretagne Sud

***

Early Modern Hot Takes offers reflections from early modern scholars on trends, topics and events we’re thinking about and living through. Our vibe is pièces de circonstance, timely and untimely.

Les spécialistes de la prémodernité réagissent aux themes et aux évènements de notre vécu contemporain. Nous visons la pièce de circonstance, sujets tendances et hors propos.

Edited by Chloé Hogg, University of Pittsburgh